There are countless resources on C/C++ available online, but I often find that, after reading some articles, it seems the authors themselves don’t fully understand what they wrote (looking back at my own earlier articles, my perspective was too one-sided and superficial at that time). Therefore, for C/C++ materials, I believe it’s essential to refer directly to the standard documentation, as standards do not introduce ambiguities. One should not blindly search the internet and trust second-hand digested materials.

I think consulting these four documents is enough for understanding the features of the C/C++ languages (click to preview online or download):

- ISO/IEC 9899:1999 (E) (C99 standard)

- The C Programming Language Second Edition (The major work of C language creators Dennis Ritchie and Brian Kernighan)

- ISO/IEC 14882:2014(E) (C++14 standard)

- The C++ Programming Language Fourth Edition (Written by the father of C++, based on the C++11 standard)

The reason the C language standard does not follow the latest C11 standard is that the current C++ standard (C++14) references ISO/IEC 9899:1999 in its Normative references, which means TCPL and TC++PL can serve as applicable descriptions for the C/C++ standards and can corroborate each other.

For more about C++ Normative references, refer to ISO/IEC 14882:2014(E) §1.2 Normative references.

I will gradually extract some commonly ambiguous language features from the standard norms here to ensure that what I write is backed by the standard documentation.

exit() behavior

function prototype:

1 | // The attribute-token noreturn specifies that a function does not return. |

The function exit() has additional behavior in this International Standard:

- First, objects with thread storage duration and associated with the current thread are destroyed. Next, objects with static storage duration are destroyed and functions registered by calling atexit are called. See 3.6.3 for the order of destructions and calls. (Automatic objects are not destroyed as a result of calling exit().)

If control leaves a registered function called by exit because the function does not provide a handler for a thrown exception, std::terminate() shall be called (15.5.1). - Next, all open C streams (as mediated by the function signatures declared in

) with unwritten buffered data are flushed, all open C streams are closed, and all files created by calling tmpfile() are removed. - Finally, control is returned to the host environment. If status is zero or EXIT_SUCCESS, an implementation-defined form of the status successful termination is returned. If status is EXIT_FAILURE, an implementation-defined form of the status unsuccessful termination is returned. Otherwise, the status returned is implementation-defined.

return statement

A function returns to its caller by the return statement.

A return statement with neither an expression nor a braced-init-list can be used only in functions that do not return a value, that is, a function with the return type cv void, a constructor (12.1), or a destructor (12.4).

A return statement with an expression of non-void type can be used only in functions returning a value; the value of the expression is returned to the caller of the function. The value of the expression is implicitly converted to the return type of the function in which it appears. A return statement can involve the construction and copy or move of a temporary object (12.2). [ Note: A copy or move operation associated with a return statement may be elided or considered as an rvalue for the purpose of overload resolution in selecting a constructor (12.8). — end note ] A return statement with a braced-init-list initializes the object or reference to be returned from the function by copy-list-initialization (8.5.4) from the specified initializer list.

1 | std::pair<std::string,int> f(const char* p, int x) { |

A return statement with an expression of type void can be used only in functions with a return type of cv void; the expression is evaluated just before the function returns to its caller.

Flowing off the end of a function is equivalent to a return with no value; this results in undefined behavior in a value-returning function. (Note: the main function does not adhere to this rule.)

Since the return value of the main function is used as the argument to std::exit, the standard explicitly states that not returning explicitly at the end of the main function is equivalent to return 0; A return statement in main has the effect of leaving the main function (destroying any objects with automatic storage duration) and calling std::exit with the return value as the argument. If control reaches the end of main without encountering a return statement, the effect is that of executing

1 | return 0; |

For a more detailed discussion on the prototype and return value of the main function, see: 关于main函数的原型和返回值

non-deduced context

The non-deduced contexts are:

- The nested-name-specifier of a type that was specified using a qualified-id.

- The expression of a decltype-specifier.

- A non-type template argument or an array bound in which a subexpression references a template parameter.

- A template parameter used in the parameter type of a function parameter that has a default argument that is being used in the call for which argument deduction is being done.

- A function parameter for which argument deduction cannot be done because the associated function argument is a function, or a set of overloaded functions (13.4), and one or more of the following apply:

- more than one function matches the function parameter type (resulting in an ambiguous deduction), or

- no function matches the function parameter type, or

- the set of functions supplied as an argument contains one or more function templates.

- A function parameter for which the associated argument is an initializer list (8.5.4) but the parameter does not have std::initializer_list or reference to possibly cv-qualified std::initializer_list type.

1

2template<class T> void g(T);

g({1,2,3}); // error: no argument deduced for T - A function parameter pack that does not occur at the end of the parameter-declaration-list.

异常抛出时的构造和析构

An object of any storage duration whose initialization or destruction is terminated by an exception will have destructors executed for all of its fully constructed subobjects (excluding the variant members of a union-like class), that is, for subobjects for which the principal constructor (12.6.2) has completed execution and the destructor has not yet begun execution.

对象析构时的执行顺序

After executing the body of the destructor and destroying any automatic objects allocated within the body, a destructor for class X calls the destructors for X’s direct non-variant non-static data members, the destructors for X’s direct base classes and, if X is the type of the most derived class (12.6.2), its destructor calls the destructors for X’s virtual base classes. All destructors are called as if they were referenced with a qualified name, that is, ignoring any possible virtual overriding destructors in more derived classes. Bases and members are destroyed in the reverse order of the completion of their constructor (see 12.6.2). A return statement (6.6.3) in a destructor might not directly return to the caller; before transferring control to the caller, the destructors for the members and bases are called. Destructors for elements of an array are called in reverse order of their construction (see 12.6).

对象构造时的执行顺序

In a non-delegating constructor, initialization proceeds in the following order:

- First, and only for the constructor of the most derived class (1.8), virtual base classes are initialized in the order they appear on a depth-first left-to-right traversal of the directed acyclic graph of base classes, where “left-to-right” is the order of appearance of the base classes in the derived class base-specifier-list.

- Then, direct base classes are initialized in declaration order as they appear in the base-specifier-list (regardless of the order of the mem-initializers).

- Then, non-static data members are initialized in the order they were declared in the class definition (again regardless of the order of the mem-initializers).

- Finally, the compound-statement of the constructor body is executed.

[ Note: The declaration order is mandated to ensure that base and member subobjects are destroyed in the reverse order of initialization. - end note ]

类的内置类型数据成员初始化

If no constructor is provided to explicitly initialize this member, its value is undefined. – 在标准12.6.2 Initializing bases and members(P268)

Note: An abstract class (10.4) is never a most derived class, thus its constructors never initialize virtual base classes; therefore, the corresponding mem-initializers may be omitted. - end note ] An attempt to initialize more than one non-static data member of a union renders the program ill-formed. [ Note: After the call to a constructor for class X for an object with automatic or dynamic storage duration has completed, if the constructor was not invoked as part of value-initialization and a member of X is neither initialized nor given a value during execution of the compound-statement of the body of the constructor, the member has an indeterminate value. - end note

1 | struct A { |

If a given non-static data member has both a brace-or-equal-initializer and a mem-initializer, the initialization specified by the mem-initializer is performed, and the non-static data member’s brace-or-equal-initializer is ignored. [ Example: Given

1 | struct A { |

the A(int) constructor will simply initialize i to the value of arg, and the side effects in i’s brace-or-equal-initializer will not take place. - end example ]

Undefined Behavior

Behavior for which this International Standard imposes no requirements [ Note: Undefined behavior may be expected when this International Standard omits any explicit definition of behavior or when a program uses an erroneous construct or erroneous data. Permissible undefined behavior ranges from ignoring the situation completely with unpredictable results, to behaving during translation or program execution in a documented manner characteristic of the environment (with or without the issuance of a diagnostic message), to terminating a translation or execution (with the issuance of a diagnostic message). Many erroneous program constructs do not engender undefined behavior; they are required to be diagnosed. - end note ]

求值顺序

C++ has no defined order of evaluation for sub-expressions in an expression. You cannot assume the expression is evaluated from left to right.

1 | // There's no definite specification whether f() or g() is called first |

And the following code:

1 | int i=1; |

The assignment behavior may execute as v[1]=1 or v[2]=1;

闭包(closure)

Let’s directly refer to the standard…

ISOIEC 14882 2014(C++14) §5.1.2 p90

**The evaluation of a lambda-expression results in a prvalue temporary (12.2). This temporary is called the **closure object. A lambda-expression shall not appear in an unevaluated operand (Clause 5), in a template-argument, in an alias-declaration, in a typedef declaration, or in the declaration of a function or function template outside its function body and default arguments. [ Note: The intention is to prevent lambdas from appearing in a signature. - end note ] [ Note: A closure object behaves like a function object (20.9). - endnote ]

The type of the lambda-expression (which is also the type of the closure object) is a unique, unnamed non-union class type - called the closure type - whose properties are described below. This class type is neither an aggregate (8.5.1) nor a literal type (3.9). The closure type is declared in the smallest block scope, class scope, or namespace scope that contains the corresponding lambda-expression. [ Note: This determines the set of namespaces and classes associated with the closure type (3.4.2). The parameter types of a lambda-declarator do not affect these associated namespaces and classes. - end note ] An implementation may define the closure type differently from what is described below provided this does not alter the observable behavior of the program other than by changing:

- the size and/or alignment of the closure type,

- whether the closure type is trivially copyable (Clause 9),

- whether the closure type is a standard-layout class (Clause 9), or

- whether the closure type is a POD class (Clause 9).

Lvalue and rvalue

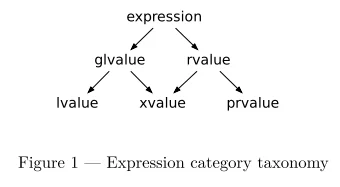

Expressions are categorized according to the taxonomy in Figure.

- An lvalue (so called, historically, because lvalues could appear on the left-hand side of an assignment expression) designates a function or an object. [ Example: If E is an expression of pointer type, then *E is an lvalue expression referring to the object or function to which E points. As another example, the result of calling a function whose return type is an lvalue reference is an lvalue. - end example ]

- An xvalue (an “eXpiring” value) also refers to an object, usually near the end of its lifetime (so that its resources may be moved, for example). An xvalue is the result of certain kinds of expressions involving rvalue references (8.3.2). [ Example: The result of calling a function whose return type is an rvalue reference is an xvalue. - end example ]

- A glvalue (“generalized” lvalue) is an lvalue or an xvalue.

- An rvalue (so called, historically, because rvalues could appear on the right-hand side of an assignment expression) is an xvalue, a temporary object (12.2) or subobject thereof, or a value that is not associated with an object.

- A prvalue (“pure” rvalue) is an rvalue that is not an xvalue. [ Example: The result of calling a function whose return type is not a reference is a prvalue. The value of a literal such as 12, 7.3e5, or true is also a prvalue. - end example ]

Every expression belongs to exactly one of the fundamental classifications in this taxonomy: lvalue, xvalue, or prvalue. This property of an expression is called its value category. [ Note: The discussion of each built-in operator in Clause 5 indicates the category of the value it yields and the value categories of the operands it expects. For example, the built-in assignment operators expect that the left operand is an lvalue and that the right operand is a prvalue and yield an lvalue as the result. User-defined operators are functions, and the categories of values they expect and yield are determined by their parameter and return types. - end note ]

{}构造不允许int->double的原因

Because if int and double occupy the same number of bits, then some such int to double conversions must lose information.

It sometimes comes as a surprise that {}-construction doesn’t allow int to double conversion, but if (as is not uncommon) the size of an int is the same as the size of a double, then some such conversions must lose information. Consider:

1 | static_assert(sizeof(int)==sizeof(double),"unexpected sizes"); |

We will not get x==y. However, we can still initialize a double with an integer literal that can be represented exactly.

char带不带符号由实现定义

It is implementation-defined whether a plain char is considered signed or unsigned. –[TCPL 6.2.3.1]

[14882:2014(E) § 3.9.1]:

A char, a signed char, and an unsigned char occupy the same amount of storage and have the same alignment requirements.

In any particular implementation, a plain char object can take on either the same values as a signed char or an unsigned char; which one is implementation-defined.

For each value i of type unsigned char in the range 0 to 255 inclusive, there exists a value j of type char such that the result of an integral conversion (4.7) from i to char is j, and the result of an integral conversion from j to unsigned char is i.

默认参数的几个反例

Default arguments for a member function of a class template shall be specified on the initial declaration of the member function within the class template.

1 | class C { |

Local variables shall not be used in a default argument. Example:

1 | void f() { |

The keyword this shall not be used in a default argument of a member function.

1 | class A { |

For more content, please refer to ISO/IEC 14882:2014(E) § 8.3.6

对象的几种初始化方式

zero-initialize

To zero-initialize an object or reference of type T means:

- if T is a scalar type (3.9), the object is initialized to the value obtained by converting the integer literal 0 (zero) to T;

- if T is a (possibly cv-qualified) non-union class type, each non-static data member and each base-class subobject is zero-initialized and padding is initialized to zero bits;

- if T is a (possibly cv-qualified) union type, the object’s first non-static named data member is zero-initialized and padding is initialized to zero bits;

- if T is an array type, each element is zero-initialized;

- if T is a reference type, no initialization is performed.

default-initialize

To default-initialize an object of type T means:

- if T is a (possibly cv-qualified) class type (Clause 9), the default constructor (12.1) for T is called (and the initialization is ill-formed if T has no default constructor or overload resolution (13.3) results in an ambiguity or in a function that is deleted or inaccessible from the context of the initialization);

- if T is an array type, each element is default-initialized;

- otherwise, no initialization is performed.

If a program calls for the default initialization of an object of a const-qualified type T, T shall be a class type with a user-provided default constructor.

value-initialize

To value-initialize an object of type T means:

- if T is a (possibly cv-qualified) class type (Clause 9) with either no default constructor (12.1) or a default constructor that is user-provided or deleted, then the object is default-initialized;

- if T is a (possibly cv-qualified) class type without a user-provided or deleted default constructor, then the object is zero-initialized and the semantic constraints for default-initialization are checked, and if T has a non-trivial default constructor, the object is default-initialized;

- if T is an array type, then each element is value-initialized;

- otherwise, the object is zero-initialized.

An object that is value-initialized is deemed to be constructed and thus subject to provisions of this International Standard applying to “constructed” objects, objects “for which the constructor has completed,” etc., even if no constructor is invoked for the object’s initialization.

Initialization of non-local variables

There are two broad classes of named non-local variables: those with static storage duration (3.7.1) and those with thread storage duration (3.7.2). Non-local variables with static storage duration are initialized as a consequence of program initiation. Non-local variables with thread storage duration are initialized as a consequence of thread execution. Within each of these phases of initiation, initialization occurs as follows.Variables with static storage duration (3.7.1) or thread storage duration (3.7.2) shall be zero-initialized (8.5) before any other initialization takes place. A constant initializer for an object o is an expression that is a constant expression, except that it may also invoke constexpr constructors for o and its subobjects even if those objects are of non-literal class types [ Note: such a class may have a non-trivial destructor - end note ]. Constant initialization is performed:

- if each full-expression (including implicit conversions) that appears in the initializer of a reference with static or thread storage duration is a constant expression (5.19) and the reference is bound to an lvalue designating an object with static storage duration, to a temporary (see 12.2), or to a function;

- if an object with static or thread storage duration is initialized by a constructor call, and if the initialization full-expression is a constant initializer for the object;

- if an object with static or thread storage duration is not initialized by a constructor call and if either the object is value-initialized or every full-expression that appears in its initializer is a constant expression.

Together, zero-initialization and constant initialization are called static initialization; all other initialization is dynamic initialization. Static initialization shall be performed before any dynamic initialization takes place. Dynamic initialization of a non-local variable with static storage duration is either ordered or unordered. Definitions of explicitly specialized class template static data members have ordered initialization. Other class template static data members (i.e., implicitly or explicitly instantiated specializations) have unordered initialization. Other non-local variables with static storage duration have ordered initialization.

Variables with ordered initialization defined within a single translation unit shall be initialized in the order of their definitions in the translation unit. If a program starts a thread (30.3), the subsequent initialization of a variable is unsequenced with respect to the initialization of a variable defined in a different translation unit. Otherwise, the initialization of a variable is indeterminately sequenced with respect to the initialization of a variable defined in a different translation unit. If a program starts a thread, the subsequent unordered initialization of a variable is unsequenced with respect to every other dynamic initialization. Otherwise, the unordered initialization of a variable is indeterminately sequenced with respect to every other dynamic initialization. [ Note: This definition permits initialization of a sequence of ordered variables concurrently with another sequence. - end note ] [ Note: The initialization of local static variables is described in 6.7.- end note ]## value and/or reference semantics

What is value and/or reference semantics, and which is best in C++?

With reference semantics, assignment is a pointer-copy (i.e., a reference). Value (or “copy”) semantics mean assignment copies the value, not just the pointer. C++ gives you the choice: use the assignment operator to copy the value (copy/value semantics), or use a pointer-copy to copy a pointer (reference semantics). C++ allows you to override the assignment operator to do anything your heart desires, however the default (and most common) choice is to copy the value.

Pros of reference semantics: flexibility and dynamic binding (you get dynamic binding in C++ only when you pass by pointer or pass by reference, not when you pass by value).

Pros of value semantics: speed. “Speed” seems like an odd benefit for a feature that requires an object (vs. a pointer) to be copied, but the fact of the matter is that one usually accesses an object more than one copies the object, so the cost of the occasional copies is (usually) more than offset by the benefit of having an actual object rather than a pointer to an object.

There are three cases when you have an actual object as opposed to a pointer to an object: local objects, global/static objects, and fully contained member objects in a class. The most important of these is the last (“composition”).

More info about copy-vs-reference semantics is given in the next FAQs. Please read them all to get a balanced perspective. The first few have intentionally been slanted toward value semantics, so if you only read the first few of the following FAQs, you’ll get a warped perspective.

Assignment has other issues (e.g., shallow vs. deep copy) which are not covered here.

Increment and decrement(prefix and postfix)

1 The user-defined function called operator++ implements the prefix and postfix ++ operator. If this function is a member function with no parameters, or a non-member function with one parameter, it defines the prefix increment operator ++ for objects of that type. If the function is a member function with one parameter (which shall be of type int) or a non-member function with two parameters (the second of which shall be of type int), it defines the postfix increment operator ++ for objects of that type. When the postfix increment is called as a result of using the ++ operator, the int argument will have value zero.

1 | struct X { |

The prefix and postfix decrement operators – are handled analogously.

Argument-dependent name lookup(ADL)

When the postfix-expression in a function call (5.2.2) is an unqualified-id, other namespaces not considered during the usual unqualified lookup (3.4.1) may be searched, and in those namespaces, namespace-scope

friend function or function template declarations (11.3) not otherwise visible may be found. These modifications to the search depend on the types of the arguments (and for template template arguments, the

namespace of the template argument).

1 | namespace N { |

For each argument type T in the function call, there is a set of zero or more associated namespaces and a set of zero or more associated classes to be considered. The sets of namespaces and classes is determined entirely by the types of the function arguments (and the namespace of any template template argument).Typedef names and using-declarations used to specify the types do not contribute to this set. The sets of namespaces and classes are determined in the following way:

- If T is a fundamental type, its associated sets of namespaces and classes are both empty.

- If T is a class type (including unions), its associated classes are: the class itself; the class of which it is a member, if any; and its direct and indirect base classes. Its associated namespaces are the innermost enclosing namespaces of its associated classes. Furthermore, if T is a class template specialization, its associated namespaces and classes also include: the namespaces and classes associated with the types of the template arguments provided for template type parameters (excluding template template parameters); the namespaces of which any template template arguments are members; and the classes of which any member templates used as template template arguments are members. [ Note: Non-type template arguments do not contribute to the set of associated namespaces. — end note ]

- If T is an enumeration type, its associated namespace is the innermost enclosing namespace of its declaration. If it is a class member, its associated class is the member’s class; else it has no associated class.

- If T is a pointer to U or an array of U, its associated namespaces and classes are those associated with U.

- If T is a function type, its associated namespaces and classes are those associated with the function parameter types and those associated with the return type.

- If T is a pointer to a member function of a class X, its associated namespaces and classes are those associated with the function parameter types and return type, together with those associated with X.

If an associated namespace is an inline namespace (7.3.1), its enclosing namespace is also included in the set. If an associated namespace directly contains inline namespaces, those inline namespaces are also included in the set. In addition, if the argument is the name or address of a set of overloaded functions and/or function templates, its associated classes and namespaces are the union of those associated with each of the members of the set, i.e., the classes and namespaces associated with its parameter types and return type. Additionally, if the aforementioned set of overloaded functions is named with a template-id, its associated classes and namespaces also include those of its type template-arguments and its template template-arguments.

Let X be the lookup set produced by unqualified lookup (3.4.1) and let Y be the lookup set produced by

argument dependent lookup (defined as follows). If X contains:

- a declaration of a class member, or

- a block-scope function declaration that is not a using-declaration, or

- a declaration that is neither a function or a function template

then Y is empty. Otherwise Y is the set of declarations found in the namespaces associated with the argument types as described below. The set of declarations found by the lookup of the name is the union of X and Y . [ Note: The namespaces and classes associated with the argument types can include namespaces and classes already considered by the ordinary unqualified lookup.

1 | namespace NS { |

When considering an associated namespace, the lookup is the same as the lookup performed when the associated namespace is used as a qualifier (3.4.3.2) except that:

- Any using-directives in the associated namespace are ignored.

- Any namespace-scope friend functions or friend function templates declared in associated classes are visible within their respective namespaces even if they are not visible during an ordinary lookup (11.3).

- All names except those of (possibly overloaded) functions and function templates are ignored.

sizeof(non-member-class)

Complete objects and member subobjects of class type shall have nonzero size.(Base class subobjects are not so constrained.)

1 | class A{}; |

When we use a C++ compiler to compile the above code, sizeof(A) will yield 1.

Derived class array conversion to base class pointer and subsequent arithmetic operations

Consider the following code:

1 | struct A{ |

The above code produces undefined behavior (usually a runtime error).

Because B is derived from A and adds its own member, so sizeof(B) > sizeof(A), assuming sizeof(A) is 8, sizeof(B) is 16, when converting a pointer of type B to a pointer of type A, the pointer arithmetic is an offset of the pointer type, that is, A type pointer a+1 corresponds to the address pointed to by a offset by 8 bytes, while B type pointer b+1 equals an offset of 16 bytes. Therefore, in callDerviedFunc only the first (x+0)->func() will succeed, and on the next iteration (x+1)->func(), since the virtual function pointer cannot be found at the expected location, it will result in undefined behavior.

The standard stipulates:

In particular, a pointer to a base class cannot be used for pointer arithmetic when the array contains objects of a derived class type.——ISO/IEC 14882:2014(E)§5.7 P120

When converting a set of derived class pointers to base class pointers, it is advisable to use standard library containers instead of raw arrays, as raw arrays cannot provide type safety like containers.

copy assignment operator

A user-declared copy assignment operator X::operator= is a non-static non-template member function of class X with exactly one parameter of type X, X&, const X&, volatile X& or const volatile X&.——ISO/IEC 14882:2014(E) §12.8 P276

[ Note: An overloaded assignment operator must be declared to have only one parameter; see 13.5.3. — end note ]

[ Note: More than one form of copy assignment operator may be declared for a class. — end note ]

[ Note: If a class X only has a copy assignment operator with a parameter of type X&, an expression of type const X cannot be assigned to an object of type X.

1 | struct X { |

Do not expect polymorphic behavior when calling virtual functions from a base class constructor

It is not possible to achieve polymorphic behavior in a base class constructor, as the base class constructor executes before the derived class:

1 | struct A |

lifetimes of objects

We can classify objects based on their lifetimes:

Automatic: Unless the programmer specifies otherwise (§12.1.8, §16.2.12), an object declared in a function is created when its definition is encountered and destroyed when its name goes out of scope. Such objects are sometimes called automatic objects. In a typical implementation, automatic objects are allocated on the stack; each call of the function gets its own stack frame to hold its automatic objects.Static: Objects declared in global or namespace scope (§6.3.4) and statics declared in functions (§12.1.8) or classes (§16.2.12) are created and initialized once (only) and ‘‘live’’ until the program terminates (§15.4.3). Such objects are called static objects. A static object has the same address throughout the life of a program execution. Static objects can cause serious problems in a multi-threaded program because they are shared among all threads and typically require locking to avoid data races (§5.3.1, §42.3).Free store: Using the new and delete operators, we can create objects whose lifetimes are controlled directly (§11.2).Temporary objects(e.g., intermediate results in a computation or an object used to hold a value for a reference to const argument): their lifetime is determined by their use. If they are bound to a reference, their lifetime is that of the reference; otherwise, they ‘‘live’’ until the end of the full expression of which they are part. A full expression is an expression that is not part of another expression. Typically, temporary objects are automatic.Thread-local objects; that is, objects declared thread_local (§42.2.8): such objects are created when their thread is and destroyed when their thread is. Static and automatic are traditionally referred to as storage classes.

Array elements and nonstatic class members have their lifetimes determined by the object of which they are part.

Giving temporary objects extended lifetimes with const T&

When we declare a const T& to reference a temporary object, it gives the temporary object an extended lifetime until the lifetime of that reference:

1 | { |

The order of destruction of the const T& follows the usual object destruction order (in reverse).

In the code above, the destruction order is e,z,y,x.

The standard defines:

1 | struct S { |

the expression S(16) + S(23) creates three temporaries: a first temporary T1 to hold the result of the expression S(16), a second temporary T2 to hold the result of the expression S(23), and a third temporary T3 to hold the result of the addition of these two expressions. The temporary T3 is then bound to the reference cr. It is unspecified whether T1 or T2 is created first. On an implementation where T1 is created before T2, T2 shall be destroyed before T1. The temporaries T1 and T2 are bound to the reference parameters of operator+; these temporaries are destroyed at the end of the full-expression containing the call to operator+. The temporary T3 bound to the reference cr is destroyed at the end of cr’s lifetime, that is, at the end of the program. In addition, the order in which T3 is destroyed takes into account the destruction order of other objects with static storage duration. That is, because obj1 is constructed before T3, and T3 is constructed before obj2, obj2 shall be destroyed before T3, and T3 shall be destroyed before obj1.

Point of declaration

1 |

|

The point of declaration for a name is immediately after its complete declarator (Clause 8) and before its initializer (if any)

1 | unsigned char x = 12; |

Note: a name from an outer scope remains visible up to the point of declaration of the name that hides it.

1 | const int i = 2; |

The point of declaration for an enumerator is immediately after its enumerator-definition.

1 | const int x = 12; |

After the point of declaration of a class member, the member name can be looked up in the scope of its class. [ Note: this is true even if the class is an incomplete class.]

1 | struct X { |

declaration and define

A declaration is a definition unless it declares a function without specifying the function’s body (8.4), it contains the extern specifier (7.1.1) or a linkage-specification 25 (7.5) and neither an initializer nor a function-body, it declares a static data member in a class definition (9.2, 9.4), it is a class name declaration (9.1), it is an opaque-enum-declaration (7.2), it is a template-parameter (14.1), it is a parameter-declaration (8.3.5) in a function declarator that is not the declarator of a function-definition, or it is a typedef declaration (7.1.3), an alias-declaration (7.1.3), a using-declaration (7.3.3), a static_assert-declaration (Clause 7), an attribute- declaration (Clause 7), an empty-declaration (Clause 7), or a using-directive (7.3.4).

template default arguments

A template-parameter of a template template-parameter is permitted to have a default template-argument. When such default arguments are specified, they apply to the template template-parameter in the scope of the template template-parameter.

1 | using namespace std; |

static object initialized of C

If an object that has automatic storage duration is not initialized explicitly, its value is indeterminate. If an object that has static storage duration is not initialized explicitly, then:

- if it has pointer type, it is initialized to a null pointer;

- if it has arithmetic type, it is initialized to (positive or unsigned) zero;

- if it is an aggregate, every member is initialized (recursively) according to these rules;

- if it is a union, the first named member is initialized (recursively) according to these rules.

compound literal of C

ISO/IEC 9899:1999 (E)

A postfix expression that consists of a parenthesized type name followed by a brace-enclosed list of initializers is a compound literal. It provides an unnamed object whose value is given by the initializer list.

1 | int *p=(int[]){1,2}; |

[[noreturn]] attribute

The attribute-token noreturn specifies that a function does not return. It shall appear at most once in each attribute-list and no attribute-argument-clause shall be present. The attribute may be applied to the declarator-id in a function declaration. The first declaration of a function shall specify the noreturn attribute if any declaration of that function specifies the noreturn attribute. If a function is declared with the noreturn attribute in one translation unit and the same function is declared without the noreturn attribute in another translation unit, the program is ill-formed; no diagnostic required. If a function f is called where f was previously declared with the noreturn attribute and f eventually returns, the behavior is undefined. [ Note: The function may terminate by throwing an exception. — end note ] [ Note: Implementations are encouraged to issue a warning if a function marked [[noreturn]] might return. — end note ]

1 | [[ noreturn ]] void f() { |

five ways of exiting a function

A return-statement is one of five ways of exiting a function:

- Executing a

return-statement. - “Falling off the end” of a function; that is, simply reaching the end of the function body. This is allowed only in functions that are not declared to return a value (i.e.,

voidfunctions) and inmain(), where falling off the end indicates successful completion. - Throwing an exception that isn’t caught locally.

- Terminating because an exception was thrown and not caught locally in a

noexceptfunction. - Directly or indirectly invoking a system function that doesn’t return (e.g.,

exit();).

A function that does not return normally (i.e., through a return or “falling off the end”) can be marked [[noreturn]].

Integer/float literal types

Simply put, an integer literal can be int/long int/long long int without a specified suffix;

| Suffix | Decimal literal |

|---|---|

| none | int/long int/long long int |

| u or U | unsigned int/unsigned long int/unsigned long long int |

| l or L | long int/long long int |

Floating-point literals are double: |

[C++11] The type of a floating literal is double unless explicitly specified by a suffix. The suffixes f and F specify float, the suffixes l and L specify long double.

| Suffix | Decimal literal |

|---|---|

| none | double |

| f or F | float |

| l or L | long double |

| This is consistent with the requirements in C and C++. |

Differences in sizeof computation periods in C and C++

Generally, the sizeof operator in C behaves at compile time, but due to C having variable length arrays (VLA), it is evaluated at runtime when its operand is a VLA array.

[C99] If the type of the operand is a variable length array type, the operand is evaluated; otherwise, the operand is not evaluated and the result is an integer constant.

1 | size_t fsize3(int n) |

In C++, sizeof and sizeof... are strictly compile-time behaviors.

[C++11] The result of sizeof and sizeof… is a constant of type std::size_t.

Relationship between C and C++ / Differences in logical operator results

Essentially, the relationship/equality/logical/ternary operator’s first-expression result in C is int (0/1), while in C++ it is of type bool.

Relational operators

[C++11] The operands shall have arithmetic, enumeration, or pointer type. The operators < (less than), > (greater than), <= (less than or equal to), and >= (greater than or equal to) all yield false or true. The type of the result is

bool.

[C99] Each of the operators < (less than), > (greater than), <= (less than or equal to), and >= (greater than or equal to) shall yield 1 if the specified relation is true and 0 if it is false. The result has typeint.

Equality operators

[C++11] The == (equal to) and the != (not equal to) operators group left-to-right. The operands shall have arithmetic, enumeration, pointer, or pointer to member type, or type std::nullptr_t. The operators == and != both yield true or false, i.e., a result of type bool.

[C99] The == (equal to) and != (not equal to) operators are analogous to the relational operators except for their lower precedence. Each of the operators yields 1 if the specified relation is true and 0 if it is false. The result has type int.

Conditional expressions

[C++11] Conditional expressions group right-to-left. The first expression is contextually converted to bool. It is evaluated and if it is true, the result of the conditional expression is the value of the second expression, otherwise that of the third expression. Only one of the second and third expressions is evaluated.

[C99] The first operand is evaluated; there is a sequence point after its evaluation. The second operand is evaluated only if the first compares unequal to 0; the third operand is evaluated only if the first compares equal to 0;

Logical operator

[C++11] The ||/&& operator groups left-to-right. The operands are both contextually converted to bool. The result is true if both operands are true and false otherwise.

[C99] The ||/&& operator shall yield 1 if both of its operands compare unequal to 0; otherwise, it yields 0. The result has type int.

Deleting an object not created by new expressions

1 | struct A |

If of class type, the operand is contextually implicitly converted (Clause 4) to a pointer to object type.

Deleting an object not created by new expressions has undefined behavior.

In the first alternative (delete object), the value of the operand of delete may be a null pointer value, a pointer to a non-array object created by a previous new-expression, or a pointer to a subobject (1.8) representing a base class of such an object (Clause 10). If not, the behavior is undefined.

C Library memory management functions do not call new/delete

The functions

calloc(),malloc(), andrealloc()do not attempt to allocate storage by calling::operator new().

The functionfree()does not attempt to deallocate storage by calling::operator delete().

If one must use malloc to allocate memory, placement new can be used:

1 | struct A |

Array names are not pointers

In the logic behind array subscript access, it is mentioned that an array name does not refer to the address of the first element of the array.

1 | int x[3][5]; |

Here x is a 3 × 5 array of integers. When x appears in an expression, it is converted to a pointer to (the first of three) five-membered arrays of integers. In the expression x[i] which is equivalent to *(x+i), x is first converted to a pointer as described; then x+i is converted to the type of x, which involves multiplying i by the length of the object to which the pointer points, namely five integer objects.

C++ and ISO C

Compatibility features in the C++11 standard

Wild Pointer and Dangling Pointer

Wild Pointer: refers to a pointer that is uninitialized (no-initializer).

ISO/IEC 14882:2014(E)

When storage for an object with automatic or dynamic storage duration is obtained, the object has an indeterminate value, and if no initialization is performed for the object, that object retains an indeterminate value until that value is replaced (5.17).

After the declaration of an uninitialized pointer x (as with int* x;), x must always be assumed to have a singular value of a pointer.

It can be seen that without initialization, the value of the pointer is undefined.

Dangling Pointer: refers to a pointer that once pointed to a meaningful address, but that address’s memory has been freed (reclaimed by the operating system).

1 | int *ivalp=new int(11); |

ISO/IEC 9899:2011(E)

If an object is referred to outside of its lifetime, the behavior is undefined. The value of a pointer becomes indeterminate when the object it points to (or just past) reaches the end of its lifetime.

Trivial default constructor

A default constructor is trivial if it is not user-provided and if:

- its class has no virtual functions (10.3) and no virtual base classes (10.1), and

- no non-static data member of its class has a brace-or-equal-initializer, and

- all the direct base classes of its class have trivial default constructors, and

- for all the non-static data members of its class that are of class type (or array thereof), each such class has a trivial default constructor.

Otherwise, the default constructor is non-trivial.

Raw string literal

The results of the following two expressions are the same.

1 | string s="\\w\\\\w"; |

In a raw string literal, a backslash is simply a backslash, and a double quote is just a double quote. They will not be escaped. Raw string literals are commonly used in regular expressions. Additionally, R"( and )" are not the only delimiters; we can include other delimiters before and after ( and ). The rule requires that the sequence of characters following the ) must exactly match the sequence preceding the ).

1 | R"***("THE STRING IS A TEST")***"; |

Also, in a raw string literal, line breaks are allowed, signifying actual new lines rather than newline characters:

1 | string s=R"("123 |

For more content, please refer to “The C++ Programming Language” p5.5/p154.

Placement syntax

If we want to place an object in a different location, we can provide an allocation function with additional parameters.

1 | class X{ |

For more details, refer to:

what is this syntax - new (this) T(); [duplicate]

Using new (this) to reuse constructors

Overriding functions do not override their original default parameters

1 |

|

Since the overriding function does not override its default parameters, the default parameter defined in class B for foo remains 1.

A virtual function call (10.3) uses the default arguments in the declaration of the virtual function determined by the static type of the pointer or reference denoting the object. An overriding function in a derived class does not acquire default arguments from the function it overrides.

Static is thread-safe initialization

[ISO/IEC 14882:2014(E) §6.8 P137]

If control enters the declaration concurrently while the variable is being initialized, the concurrent execution shall wait for completion of the initialization.

The implementation must not introduce any deadlock around execution of the initializer.

Static objects are essentially syntactic sugar for thread-safe initialized global variables.

Non-local static initialization

[ISO/IEC 14882:2014 §3.6.2.4] It is implementation-defined whether the dynamic initialization of a non-local variable with static storage duration is done before the first statement of

main.

This means that the dynamic initialization of non-local static storage duration variables is completed before the execution of the first statement in the main function (implementation-defined).

1 | struct A{ |

Order of evaluation of function parameters

1 | int i; |

The C++ standard specifies that the side effects of argument evaluations are sequenced before the function is entered.

[ISO/IEC 14882:2014 §5.2.2.8] All side effects of argument evaluations are sequenced before the function is entered.

Therefore, the output of the above code is 34. This can also be seen from the IR code perspective, observing how the compiler implements this feature:

1 | define i32 @main() #4 { |

It can be seen that when executing f(i++), the compiler first increments i, then passes the value before the increment (%1) as the argument to f. Upon entering function f, since the static object i’s value has already been modified in the main function (%2), it outputs 3 and 4 respectively.

VLA cannot have initializers

[ISO/IEC 9899:1999] The type of the entity to be initialized shall be an array of unknown size or an object type that is not a variable length array type.

Thus, the following is incorrect:

1 | int ivlan; |

The correct approach is to determine the size of the array at runtime and assign values to its members one by one, which can be done using a for loop or memset:

1 | int fuck; |

Template appearing on the right side of ./-> and ::

A name prefixed by the keyword template shall be a template-id or the name shall refer to a class template. [ Note: The keyword template may not be applied to non-template members of class templates. - end note ] [ Note: As is the case with the typename prefix, the template prefix is allowed in cases where it is not strictly necessary; that is, when the nested-name-specifier or the expression on the left of the -> or . is not dependent on a template-parameter, or the use does not appear in the scope of a template. - end note ]

1 | template <class T> struct A { |

Note the distinction from typename; typename appears before the name it qualifies, while template appears immediately before the template name.

What is Object in C++ Standard?

[ISO/IEC 14882:2014] An object is a region of storage. [ Note: A function is not an object, regardless of whether or not it occupies storage in the way that objects do. - end note ] An object is created by a definition (3.1), by a new-expression (5.3.4) or by the implementation (12.2) when needed. The properties of an object are determined when the object is created.

Description of polymorphism in the C++ Standard (C++14)

What is polymorphic?

Some objects are polymorphic (10.3); the implementation generates information associated with each such object that makes it possible to determine that object’s type during program execution.

What is polymorphic class?

Virtual functions support dynamic binding and object-oriented programming. A class that declares or inherits a virtual function is called a polymorphic class.

What is polymorphic behavior?

A base class subobject might have a polymorphic behavior (12.7) different from the polymorphic behavior of a most derived object of the same type.

The standard does not specify how compilers should implement polymorphism, so its implementation relies on the compiler. Most compilers use a virtual function table to calculate offsets, and if the code involves direct access to the virtual function table, it may have little portability (across compilers). Therefore, one cannot assume all compilers implement the virtual function table in the same way (e.g., whether to merge virtual function tables in multiple inheritance).

Class object size

Complete objects and member subobjects of class type shall have non-zero size.

Complete objects and member subobjects of class type shall have nonzero size. (Base class subobjects are not so constrained.)

Base class subobjects may be of zero size.

A base class subobject may be of zero size.

And the standard description of its sizeof:

The size of a most derived class shall be greater than zero (1.8). The result of applying sizeof to a base class subobject is the size of the base class type. When applied to an array, the result is the total number of bytes in the array. This implies that the size of an array of n elements is n times the size of an element.

References are not pointers

Earlier in an article, an author analyzed the way references are implemented in the compiler and insisted that references are pointers. This is incorrect.

First, look at how g++/clang++ implements it:

1 | int x=1234; |

Then view the LLVM-IR code of the above (irrelevant parts omitted):

1 | %6 = alloca i32, align 4 |

It can be seen that after compilation, references and pointers appear the same. However, this does not mean that references are pointers.

[ISO/IEC 14882:2014] A reference can be thought of as a name of an object.

In C++, there are no requirements for how features must be implemented; thus, saying that references are pointers is misleading.

Type of this

[ISO/IEC 14882:2014] The type of this in a member function of a class X is X*. If the member function is declared const, the type of this is const X*, if the member function is declared volatile, the type of this is volatile X*, and if the member function is declared const volatile, the type of this is const volatile X*.

I reviewed the C++98/03/11/14 standards and found no differences among them.

Differences between typedef and using

Both typedef and using can define a type alias, but why have two keywords with such similar functionality?

For using, it can not only introduce aliasing but also bring a namespace into the name lookup scope. From the perspective of declaring an alias, their most critical distinction is whether or not template aliases can be defined. typedef can achieve what using can, but the reverse is not true. I believe typedef remains mainly for C compatibility.

Here is the C++ standard’s description regarding the restrictions on typedef:

[ISO/IEC 14882:2014] It has the same semantics as if it were introduced by the typedef specifier. In particular, it does not define a new type and it shall not appear in the type-id.

To use template aliases (template alias), only using can be used.

1 | template<typename T> |

dynamic_cast failure

The behavior of pointer and reference conversions using dynamic_cast on failure differs; in pointer conversion, it returns a null pointer, while in reference conversion, it throws a std::bad_cast exception, as detailed in the C++ standard:

[ISO/IEC 14882:2014] The value of a failed cast to pointer type is the null pointer value of the required result type. A failed cast to reference type throws an exception (15.1) of a type that would match a handler (15.3) of type

std::bad_cast(18.7.2).

Implementation-defined behavior

[ISO/IEC 14882:2014] contains an Index of implementation-defined behavior:

Name hiding

1 | struct Astruct{ |

The code above presents two issues:

- In the global scope, when using the identifier

Astruct, is the identifier the class Astruct or int object Astruct? - When using the global scope’s

::Astructin the main function, which identifier is being used, the class Astruct or the int object Astruct?

Firstly, regarding the first question, using the identifier Astruct in the global scope refers to the class type identifier:

A class name (9.1) or enumeration name (7.2) can be hidden by the name of a variable, data member, function, or enumerator declared in the same scope. If a class or enumeration name and a variable, data member, function, or enumerator are declared in the same scope (in any order) with the same name, the class or enumeration name is hidden wherever the variable, data member, function, or enumerator name is visible.

This indicates that within the same scope, class names hide all identifiers with the same name.

As for the second question: using ::Astruct in the main function refers to the int object Astruct. If the class name Astruct is to be used, it must be explicitly specified:

1 | struct ::Astruct Aobj; |

A class declaration introduces the class name into the scope where it is declared and hides any class, variable, function, or other declaration of that name in an enclosing scope (3.3). If a class name is declared in a scope where a variable, function, or enumerator of the same name is also declared, then when both declarations are in scope, the class can be referred to only using an elaborated-type-specifier (3.4.4).

Several ways to implement abstract base classes

The concept of abstract classes as defined in the C++ standard is:

An abstract class can also be used to define an interface for which derived classes provide a variety of implementations.

An abstract class is a class that can be used only as a base class of some other class; no objects of an abstract class can be created except as subobjects of a class derived from it. A class is abstract if it has at least one pure virtual function. [ Note: Such a function might be inherited: see below. — end note ]

A class is abstract if it contains or inherits at least one pure virtual function for which the final overrider is pure virtual.

Here, there are two concepts:

- Objects of abstract classes cannot be created, except as subobjects of derived classes.

- At least one pure virtual function must be present.

Pure virtual functions are not the only way to create abstract classes; any method that ensures no object can be created qualifies as an abstract class. This can be achieved by defining the constructor as protected (since the derived class’s constructor will call the base class’s constructor, we should ensure that the derived class has access):

1 | struct A{ |

Of course, this method is quite blunt. This method can also facilitate the following two operations (in a multi-inheritance hierarchy, it can be defined as private):

- Allow allocation of objects only on the stack by defining

operator newandoperator deletemember functions as protected. - Allow allocation of objects only on the heap by defining the

destructormember function as protected.

If there is no compelling reason to define a member function as pure virtual, the destructor can also be defined as pure virtual:

1 | struct A{ |

However, this is not a good idea, as the derived class’s destructor will implicitly call the base class’s destructor. This means that when a destructor is defined as pure virtual, it must provide an implementation; otherwise, a linking error will occur. This contradicts the definition of pure virtual functions:

A function declaration cannot provide both a pure-specifier and a definition.

1 | struct C { |

In C++, there are many ways to implement behavior, but not all methods are the best; it is important to fit one’s needs.

Pointer comparison behavior

Comparing pointers to objects is defined as follows:

- If two pointers point to different elements of the same array, or to subobjects thereof, the pointer to the element with the higher subscript compares greater.

- If one pointer points to an element of an array, or to a subobject thereof, and another pointer points one past the last element of the array, the latter pointer compares greater.

- If two pointers point to different non-static data members of the same object, or to subobjects of such members, recursively, the pointer to the later declared member compares greater provided the two members have the same access control (Clause 11) and provided their class is not a union.

subobjects in C++

[ISO/IEC 14882:2014] Objects can contain other objects, called subobjects. A subobject can be a member subobject (9.2), a base class subobject (Clause 10), or an array element.

From this perspective, if you want to implement inheritance of data members in C, you only need to include a struct base member in struct derived. It is quite interesting to try to implement OO features using C; I will analyze this for a while and write an article about it.